A recent spate of reports and studies suggest that antibodies made when having COVID-19 might not last long — maybe from a couple of months to simply a few weeks. This raises concerns regarding our ability to build immunity to COVID-19, at least by natural means, yet as heightening concerns regarding the potential for reinfection.

“The results require caution concerning antibody-based ‘immunity passports,’ herd immunity, and perhaps vaccine sturdiness,” a recent correspondence within the New England Journal of Medicine stated, though the column noted the further study is required. But antibodies aren’t the be-all and end-all of conferred immunity, specialists say. And it’s still early days within the study of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

“Existing antibody research shows that the strength of the immune response correlates to the severity of the symptoms. The sickest individuals tend to have more antibodies circulating in the bloodstream compared to those with mild or no symptoms,” said Chris DiPasquale, director of assay development at Babson Diagnostics, a Texas company doing COVID-19 serology (antibody) tests.

In terms of developing a strong COVID-19 vaccine, the way our bodies’ natural immune systems react might not have as strong a bearing on vaccine effectiveness as common sense dictates.

One common theme with existing COVID-19 research is that we still don’t have enough time or data to effectively and thoroughly understand the disease.

One thing that fading antibodies might indicate, however, is the need for a series of shots and perhaps regular “re-ups” of vaccination once one is available.

Even with evidence of fading antibodies, reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 is unlikely because of what we generally know about immune reaction to viruses, researchers say.

For most, it’s simply that the pathology of this virus isn’t well understood. What might seem like reinfection could simply be longer-term effects of the virus, or reemergence of viral propagation inside someone who feels better but never fully cleared the effective virus from their system.

A person’s immune system involves a complex array of interrelated cell actions, productions, and associated responses to defeat a disease.

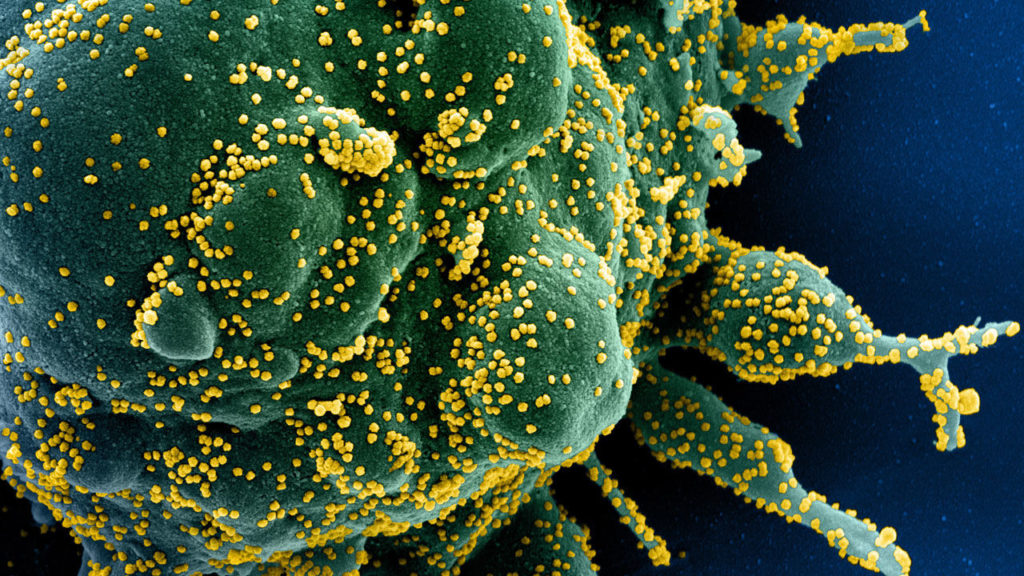

When a body encounters a virus, B cells, aided by “helper” T cells, create neutralizing antibodies that attack and destroy future instances of the virus before a person gets sick.

These antibodies are among the easiest to detect and thus have been the most commonly reported measure of COVID-19 immunity.

But two types of T cells, which are harder to measure, also play an important role in determining immunity and aren’t always perfectly correlated to antibody levels.

One preprint study from researchers at Strasbourg University Hospitals in France, for instance, found T cell responses in people with COVID-19 even when antibody tests came up negative.

Finally, a further study in the journal Nature found antiviral responses that go beyond these immune cells altogether.